From 1991 to 1994, over 35,000 Haitians were detained in Camps McCalla and Bulkeley at Guantánamo. Most refugees were fleeing an oppressive and unstable military regime, which came to power in Haiti after a violent coup. Following an earlier arrangement, the Coast Guard picked up Haitian refugees at sea in order to prevent their boats from capsizing or landing in the United States, and took them to Guantánamo instead.

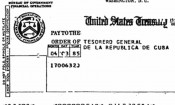

Because the United States government maintained that under the terms of the lease agreements, Guantánamo was not American soil, the Haitians detained there were barred from receiving legal assistance to help petition for asylum. Legally, there were no restraints on how immigration officials exercised administrative law in regard to Haitian asylum pleas from Guantánamo, and the American military became the sole sovereign entity controlling Haitians’ daily lives as detainees. Life in the camps descended into violation of international human rights’ laws. Overcrowding, rotten food, and no access to legal counsel created abhorrent conditions. This situation’s “legality” hinged on the government’s position that Guantánamo was not American territory.

Despite the threats of retribution, torture, and murder, most refugees were returned to Haiti, despite United Nations’ protocol prohibiting the return of endangered refugees, which the United States had agreed to in 1967. (Officially, the United States government claimed that returning Haitian refugees did not face persecution.) Approximately three hundred HIV-positive Haitian refugees, whom Haiti refused to accept, remained at Guantánamo until a federal court ruled in June 1993 that their indefinite detention was illegal.

- Rutgers University

Because the United States government maintained that under the terms of the lease agreements, Guantánamo was not American soil, the Haitians detained there were barred from receiving legal assistance to help petition for asylum. Legally, there were no restraints on how immigration officials exercised administrative law in regard to Haitian asylum pleas from Guantánamo, and the American military became the sole sovereign entity controlling Haitians’ daily lives as detainees. Life in the camps descended into violation of international human rights’ laws. Overcrowding, rotten food, and no access to legal counsel created abhorrent conditions. This situation’s “legality” hinged on the government’s position that Guantánamo was not American territory.

Despite the threats of retribution, torture, and murder, most refugees were returned to Haiti, despite United Nations’ protocol prohibiting the return of endangered refugees, which the United States had agreed to in 1967. (Officially, the United States government claimed that returning Haitian refugees did not face persecution.) Approximately three hundred HIV-positive Haitian refugees, whom Haiti refused to accept, remained at Guantánamo until a federal court ruled in June 1993 that their indefinite detention was illegal.

- Rutgers University